To Your Health: When a simple cut becomes a fight for life

- Guest Writer

- Jul 30, 2025

- 5 min read

By Jeremy Berger, DO, MS, MPH and Ann Backus, MS, Harvard Chan School for Public Health

It was midmorning and you were hauling traps when a rusty piece of metal scraped your hand. It lashed across the back of your left hand — fast and deep — opening a jagged laceration that cut through skin and muscle. Saltwater stung, but there were still traps to haul, and the sun was still high. You rinsed the wound in seawater and wrapped it with a bait-slick rag from the deck, thinking you would deal with it later.

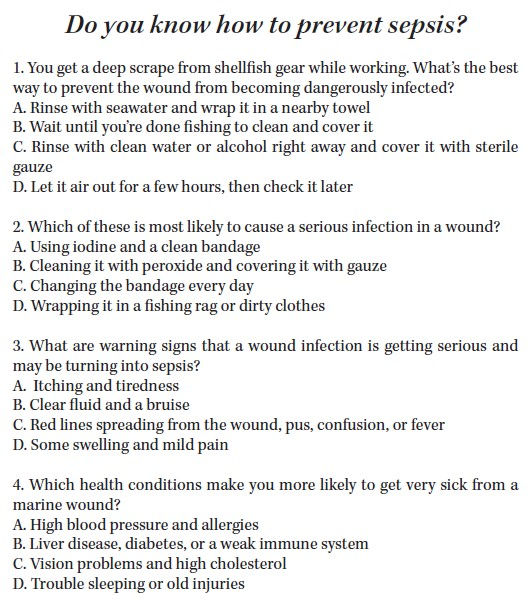

Take the quiz and see if you've got what it takes to stop sepsis before it starts. Answers at the bottom!

The rag was soaked with fish slime, brine, and whatever else had been ground into it over weeks at sea. Beneath that makeshift bandage, the wound stayed warm, wet, and dark — the perfect breeding ground for bacteria. You didn’t know it then, but something dangerous had already gotten into the wound.

Day 1: The Invasion

Somewhere in the folds of that gash, a microscopic marine predator — likely Vibrio vulnificus — had entered your bloodstream. You’ll often find it in warm coastal waters, especially where the tide washes over shellfish beds and shallows.

By the time you made it back to shore, the pain had sharpened, the throbbing pulsed deeper. Still, it wasn’t the worst you’d felt. You went home and crashed, figuring the wound would scab over by morning. But it didn’t. Instead, the bacteria quietly spread, digging deeper into your tissue, turning a minor wound into something far more serious.

Day 2: Local Infection

The next morning, your hand was swollen and red, hot to the touch. Yellow pus oozed from the wound, and red streaks, like fine lightning bolts, crept up your forearm. That was your body trying to fight the bacterial invader: immune cells flooding the area, white blood cells deploying, inflammation ramping up.

You felt feverish and chilled, your heart was racing a little, but you told yourself it was nothing. You’ve worked through worse. So you went out fishing again. And the infection dug in deeper.

Day 2: Early afternoon

By now, the infection wasn’t just in your hand, it was in your blood. Bacteria had broken through soft tissue and entered the bloodstream. Your immune system, launched a full-scale assault: a cytokine storm.

By afternoon your crew noticed you were breathing rapidly and looked very pale. You agreed with the crew that you felt woozy and confused, and the crew took command of the boat. They headed back to shore and enroute made a Mayday call to the U.S. Coast Guard who arranged to have an ambulance waiting at the dock.

It was a good thing that the crew took action and made the Mayday call. Little did they know that the cytokines, a type of chemical messenger that usually helps by signaling the immune system to react to invading pathogens, were being produced in large amounts in response to your wound. The overabundance of cytokines, also known as a cytokine storm, can be life-threatening. Symptoms include redness, heat, swelling and pain, pale and clammy skin, and disorientation. Other observable symptoms include a rapid pulse, greater than 90 beats per minute, and rapid respiration of more than 20 breaths per minute.

Had they had a blood pressure cuff on board, the crew might have noticed that your blood pressure was decreasing.

Day 2: Late afternoon

The ambulance met you at the dock and delivered you to the ER. The doctors took one look and rushed you to critical care. Your hand was purple and black around the wound. Your blood pressure was low and respiratory rate and pulse high. You were in transition from sepsis to septic shock. Doctors provided intravenous fluids and started antibiotics. They cultured and debrided your wound. The culture confirmed the presence of the bacterium, Vibrio vulnificus.

Had your crew not responded to your physical appearance that afternoon on the boat, you would have reached the point of septic shock. In spite of being on a ventilator and heart support, your organs might have been unable to recover from the inflammation that had invaded your body and caused a sudden overabundance of cytokines to be released.

A Cautionary Tale

Those who fish along the Northeast coast are not familiar with V. vulnificus, as it is known scientifically. It has been common along the Gulf of Mexico coast for years because it prefers warm, brackish water. However, we in the Northeast need to pay attention now. Global Climate Models (GCMs) and patient surveillance data have documented the increased presence of V. vulnificus and cases of infection from 1988-2018 along the entire East Coast as far north as Maine due to the increase in ocean temperatures.

We also need to pay attention to wounds originating in seawater because “V. vulnificus is the most pathogenic of the Vibrio genus: wound infection mortality rates are as high as 18% and fatalities have occurred as soon as 48 hours following exposure,” according to a 2023 article. The article’s authors also point out that these wounds “…can quickly turn necrotic requiring surgical tissue removal or limb amputation in around 10% of cases.”

Finally, people with compromised immune systems, diabetes or liver disease are at greater risk for a serious illness outcome from V. vulnificus exposure. In addition to the environment associated with fishing and coastal recreation, V. vulnificus may well be present when inland flooding from hurricanes and coastal flooding brings seawater inland. Historically, it was the cause of five fatalities during Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans.

Think you now know how to take care of saltwater wounds? Take the quick quiz in the box below and see if you’ve got what it takes to stop sepsis before it starts.

Did you get all the questions right? If yes, congratulations. You may have saved your own life. If not, take note. Sepsis is unforgiving. It doesn’t wait for your fishing day to end or for the boat to dock. One missed step — a dirty wound, a delayed response — can determine whether or not you fish in the future. Learn the signs. Carry what you need to keep wounds clean. Train your crew, because out there, far from shore, you and your crew are the first responders.

Epilogue

Thanks to the 2024 Maine EMS Medical Shock Protocol, the fight against sepsis now begins the moment help arrives. Paramedics are trained to spot the early signs — infection, fever, low blood pressure, confusion — and when they suspect sepsis, they act fast. “Code Sepsis” is declared right there on scene. Fluids are started immediately. The hospital is alerted before the ambulance even moves. It’s no longer a waiting game. It’s a race, and now it starts earlier than ever.

This year, World Sepsis Day will take place on September 13. You can bring awareness to your community by visiting www.worldsepsisday.org and sharing the information in this article with friends and family.

Quiz Answers: 1-C; 2-D; 3-C; 4-B.

Comments